What Are Robots?

As I read the Palkovice history from the city's website, I came across these sentences: "In addition to these regular land salaries, the Myslikov family was originally obliged to work at the Kozlovice court. However, according to the record in the land register, they were relieved of this obligation for the amount of 5 gold payable for the New Year and for St. John the Baptist. But they did not get rid of the robot completely. Under the express condition, they remained obliged to work on the castle and to build others."

Then, in the very next paragraph, I found this: "The subjects, who paid the benefits with a robot, worked at the lord's courts."

But they did not get rid of the robots completely? They paid benefits with a robot?

Just what was a robot doing working on a castle in what is now Czechia in the 16th century? I thought robots had been "invented" in the early 20th century. Was Palkovice technologically advanced for its time? Images such as this photo of a shiny white robot posed as Auguste Rodin's famous statue, The Thinker, filled my mind.

Actually, Karel Čapek "repurposed" the Czech and Slovak word "robota" for his 1920 play, R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots. In the play, a scientist discovers the secret of creating humanlike machines that are more precise and reliable than human beings. Years later. the machines dominate the human race and threaten it with extinction, though at the last moment humanity is saved. For this play, Čapek's brother, Josef, repurposed robot from its original concept where robota referred to the serf's obligations to perform work for the lord who owned the land and property where they lived in return for things they needed from those lords. So was born the modern sense of robot as an "artificial" being.

The original robota referred to required work performed for the lord who lived in the castle to repay debts owed to him. But, since he owned all the land and everything on the land, the serfs quickly found themselves a lots of robots to the lord. As you can probably guess, the serfs soon accumulated enough robots to require them to work four or five days for the lord, leaving them very little time left to do any work for themselves or their families. At such times, there were even "strikes" by the serfs demanding reductions in the demands of the robots.

A petition of landowners and landless people in 1848 was signed by about 16,000 people. In the petition, "homemakers and subspecies" (landless people?) complained that due to low income, they could not have representatives in elected bodies. This petition was handed to the Provincial Assembly in Brno on April 19, 1848. It demanded not only the abolition of robots, but also the extension of the right to vote to less affluent citizens and, above all, the allocation of land owned by the nobility for homemakers and landless people. The robot system and baliffs appointed by the lord to oversee the villages were finally eliminated in 1848, with the baliffs who were appointed by the lord, and oversaw the functioning of the village, being replaced by elected mayors.

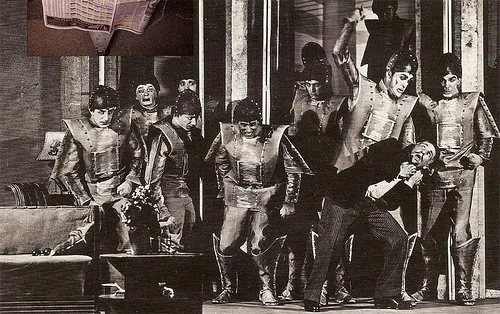

As for Čapek's play, it begins in a factory that makes artificial people, called roboti, from synthetic organic matter. They are not exactly robots by the current definition of the term; they are living flesh and blood creatures rather than machinery and are closer to the modern idea of clones, but they are assembled, not grown. They may be mistaken for humans and can think for themselves. They seem happy to work for humans at first, but a robot rebellion nearly leads to the extinction of the human race.

R.U.R. quickly became famous and was influential early in the history of its publication. By 1923, it had been translated into thirty languages. But it wasn't necessarily a great literary work. Isaac Asimov, author of the Robot series of books and creator of the Three Laws of Robotics, stated: “Capek’s play is, in my own opinion, a terribly bad one, but it is immortal for that one word. It contributed the word ‘robot’ not only to English but, through English, to all the languages in which science fiction is now written.”

Actually, Asimov is being a little unfair in his quote, after all, he wrote the Three Laws of Robotics to prevent the very situation that occurs in Čapek's play. Also, it has had a role in episodes of TV shows and movies ranging from the original Star Trek series, to Dr. Who, Blake's 7, The Outer Limits, and other U.S. and British TV shows, as well as having echoes in such robotic beings as the Terminator, HAL 9000, and Blade Runner’s replicants.