A small man sitting on top of a pile of money—what a great picture of the rentier class. They make money the old fashioned way—they sit on their money while the money multiplies of its own accord without having to exhaust themselves with their labor. Their money multiplies even faster than bunny rabbits.

Economic rent is the unearned value within a profit. The term “rentier” refers to someone who obtains private capture of this unearned value. In other words, the rentier is someone who receives profit from some other basis than their own productive activity. Rentier profit is distinguished from capitalist profit. The capitalist accrues value from others’ labor, but needs to re-invest that a portion of that profit to remain competitive. The capitalist is interested in productive activity, while the rentier is under no such compulsion to invest in productive activity, but simply collects the money without any other interest in the source of that money.

After I graduated from college, I went to work for Gulf Oil as a technical programmer, and worked there for five years. Something I found amazing at the time was how many people there had worked for the company for years already. My manager had worked for Gulf for 20 years, while the director had worked for Gulf for 35 years. One man in my group had worked for the company almost 50 years, and his dad had worked for Gulf before him.

Gulf Oil was what I later decided to call an "old school" corporation with management that thought it hired good employees, and tried to keep them working for the company—they paid above average salaries for the oil industry, had an excellent pension system, had good health benefits, and plentiful vacation time. Management knew that, while that might be more expensive in the short term, they were investing in human capabilities, and it was cheaper to do this in the long run than having to hire and train new employees who did not have the benefit of experience. The employees won, the company won, and even the shareholders benefitted.

My job with Gulf Oil came to an end in early 1986, after Chevron Oil officially took over the portion of Gulf I worked in.

From Wikipedia:

Pickens made loud criticisms of the existing Gulf management and offered an alternative business plan intended to release shareholder value through a royalty trust that management argued would "slim down" Gulf's market share. Pickens had acquired the reputation of being a corporate raider whose skill lay in making profits out of bidding for companies but without actually acquiring them. During the early 1980s alone, he made failed bids for Cities Service, General American Oil, Gulf, Phillips Petroleum and Unocal. The process of making such bids would promote a frenzy of asset divestiture and debt reduction in the target companies. This is a standard defensive tactic calculated to boost the current share price, although possibly at the expense of long-term strategic advantage. The target shares would rise sharply in price, at which point Pickens would dispose of his interest at a substantial profit.

T. Boone Pickens was an almost perfect example of a rentier capitalist, that is, a person who makes money without doing any productive work, and risking little or none of his own assets. In fact, he made money by damaging the long-term health of the companies he targetted.

The Wikipedia article also mentions "shareholder value," which is a complete fiction, as I will show later. Although shareholders own equity in a company, they do not own the company. The claim that they own the company enables another form of rentier capitalism that has been very destructive to the U.S. and world economies.

Gulf divested many of its worldwide operating subsidiaries, and was then acquired by Standard Oil of California (SOCAL) in the spring of 1985. (SOCAL changed its name to Chevron before it began the acquisition process.) The Mesa group of investors, led by T. Boone Pickens, was reported to have made a profit of $760 million ($1,914.8 million today) when it assigned its Gulf shares to Chevron. Chevron gave the Gulf Oil CEO, James Lee, and the other senior executives $11 million so they would not object to the Chevron acquisition of Gulf.

By the way, although the Wikipedia article and most other articles about the event refers to the deal between Chevron and Gulf as a "merger," that was not the case at all. Chevron acquired Gulf Oil to gain access to Gulf's oil reserves in the continental U.S. It had also acquired two refineries in the process, one in Port Arthur, Texas, and the other in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It sold both refineries as soon as it was legally permitted to do so and it could find buyers for the refineries. It also sold most of the other Gulf Oil properties it had acquired.

Most of the Gulf workers received severance packages during the year between the acquisition and the legal takeover of Gulf Oil in the spring of 1986. I was given the opportunity to move to Santa Clara, California, but, without a pay raise, that meant I would have been taking a significant pay cut. The severance package was much more attractive. Many of the Gulf employees who chose to stay with Chevron were approaching retirement under the Gulf pension plan, and chose to stay with Chevron to get full pension. They also knew that getting another job at their age would be difficult. From my contacts with some of these people, Chevron cut their pay by up to 50 percent after the one year federally-mandated "hold" expired to bring their compensation in line with the much younger employees in Chevron.

This is a short essay on rentier capitalism which I consider a major problem in society. I am not economist. I do not have economic training. But I do have eyes to see the world around me, and I think someone has to be willfully blind to avoid seeing that we are living in a world of rentier capitalism, and that is causing huge problems in society.

I will outline some of the major components of how the rentier class "earns" their wealth, and how this turns most other people into the precariat class, where the precariat class consists of all those people who live lives of "quiet desperation"—people whose jobs and incomes are insecure and may disappear tomorrow just because a financial analyst working for a Wall Street company 2,000 miles away decides this is what the company needs to do to increase profits.

Adam Smith categorized income into wages, profit and rent. Wages are earned from employment while producing a good or service; profits are earned at the risk of capital from people or firms selling a good or service for greater than the cost of production. Profit can also come from investors lending to individuals or companies so they can produce physical goods or services. Both wages and profit can be considered productive.

In contrast, "economic rent" refers to “unearned income,” where economic rents redistribute income from the majority to the rent seekers and increase inequality. Economic rent refers to people and companies who make money by doing little to no work, and risk little or none of their own assets. Rent-seeking means getting an income not as a reward for creating wealth but by grabbing a larger share of the wealth produced by other people. John Maynard Keynes described the rentier as a "functionless investor." Another word that might be used to describe those who take, but don't give anything in return is "parasite."

…there are two ways to become wealthy: to create wealth or to take wealth away from others. The former adds to society. The latter typically subtracts from it…—Joseph Stiglitz

Rentiers derive income from possession of assets that are scarce or artificially made scarce. Most familiar is rental income from land, property, minerals or financial investments, but other sources are possible, too. Economic rent can come from ownership of land and just “renting” it out for money. It can come from a firm that has a monopoly and can set the price independent of supply and demand considerations. It can be from government monopoly granting control of other “land” like rivers, broadband spectrum, or “mineral rights” of land. It can come from control of financial assets, such as capital gains, dividends, and interest on loans (especially usury). It can also come from political favors from the government, including special tax cuts and deductions granted to a small group of people or companies that give them a competitive advantage.

Rent seeking can be any of the following items:

An excellent example of windfall profits is the increased corporate profits during early 2022. Even as corporations claim the price increases are simply due to inflation, the CEOs of these corporations are claiming much higher profits, giving shareholders larger dividends, and buying stock back in record amounts. For more information, see Revealed: top US corporations raising prices on Americans even as profits surge.

Similarly, General Motors profits jumped 49% between the full years in 2019 and 2021 despite selling about a million fewer vehicles. The company said it focused on moving more expensive trucks and SUVs than in previous years, but it also raised prices—a Silverado pickup can now cost over $5,000 more than it did in 2019. That includes two rounds of March price increases just weeks after GM announced record profits and margins.

Rent seeking can also include such items as:

Rentier capitalism is the monopolization of access to any kind of property, whether that property is physical, financial, or intellectual, thereby gaining significant amounts of profit without any contribution to society. There are two main problems with rentier capitalism. First, rentiers are inclined to sit on and sweat their income-generating assets, rather than innovate; it is a recipe for economic stagnation. And second, because incomes accrue disproportionately to the asset-owning elite, it is an engine for growing inequalities of both income and wealth.

Guy Standing explains what he views as The Five Lies Of Rentier Capitalism:

A great example is the Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) between Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, and the United States. The economy of the United States so dwarfs the total economy of the six other countries that there is nothing the U.S. really needs from those countries that it can't get elsewhere. But the agreement gives foreign investors a very large say in governing those countries such because the investors can challenge countries if they try to enact domestic laws that might interfere with the profits of the company, including consumer and environmental protection laws.

Many patented inventions are based on publicly subsidized research. It is the public that pays, through taxes that finance the research, higher prices for patented products and loss of the intellectual commons. And most innovations that yield large returns through patents and so on are the result of a series of ideas and experiments attributable to many individuals or groups. Even worse, corporations also spend a lots of money on developing patents that they then use to block innovation by others.

In fact, trade and investment accords most often lead to ecological and environmental problems that are then wrtten off as "externalities" that encourage even more problems. And they rarely lead to sustainable growth over time.

Instead, the profits go to the rentiers who collect their money obtained from the financialization of everything, and from IP "rights" that block risk taking.

The army of people who work in minimum wage jobs that don't provide enough money for it to be considered a "living wage" stand testament to that lie. There are also the task rabbits, door dashers and uberers who get less than minimum wage because they are considered "independent contractors."

Adam Smith was not referring to the conservative mantra that "free markets" mean a market free of government regulations when he wrote about "free markets" in his book, Wealth of Nations. Rather, he was referring to markets free of the rentier class, who do not contribute anything of value to the market. A market that is "free" from anti-rentier regulation is a market where all freedom is gathered into the hands of a few parasitic toll-collectors who get to exact ever-higher tolls from the productive sector.

Even if you accept the conservative version of what free market means, there is no such thing as a "free market." Free markets do not exist in nature. The “free market” depends on laws and rules. The problem is, if you have enough money, you can lobby (that is, bribe) legislators to make changes in those laws and rules that make you even more money. It's not really "free" at all.

The economist Karl Polanyi questioned whether a free market can exist, such that it is completely free of distortions of political policy. He claimed that even the ostensibly freest of markets require a state to exercise coercive power in some areas, namely to enforce contracts, govern the formation of labor unions, spell out the rights and obligations of corporations, shape who has standing to bring legal actions, and define what constitutes an unacceptable conflict of interest.

The free market doesn’t exist. Every market has some rules and boundaries that restrict freedom of choice. A market looks free only because we so unconditionally accept its underlying restrictions that we fail to see them. How ‘free’ a market is cannot be objectively defined. It is a political definition. The usual claim by free-market economists that they are trying to defend the market from politically motivated interference by the government is false. Government is always involved and those free-marketeers are as politically motivated as anyone. Overcoming the myth that there is such a thing as an objectively defined ‘free market’ is the first step towards understanding capitalism.—HaJoon Chang

Neoliberalism demands that businesses should be deregulated, taxes should be cut, government operations should be privatized, and the so-called welfare state should be disassembled. According to Will Kenton in Investopedia:

Neoliberalism is a policy model that encompasses both politics and economics and seeks to transfer the control of economic factors from the public sector to the private sector. Many neoliberalism policies enhance the workings of free market capitalism and attempt to place limits on government spending, government regulation, and public ownership.

By doing all of these things, the "market" would be allowed to work its magic. But, remember, from my comments about the "free market," there is no such thing as a free market—it is nothing more than a convenient fiction that enables the rentiers to collect their money for nothing, even as they trumpet the claim that their wealth is raising all ships.

Although it can be traced back to the 19th century with its "free market capitalism" and robber barons, it really began its rise in the 1980s as western oligarchs appointed Ronald Reagan president of the United States and Margaret Thatcher as prime minister of the United Kingdom.

An interesting read about neoliberalism can be found in the essay, Neoliberalism: the idea that swallowed the world. Stephen Metcalf starts the article by writing:

The word has become a rhetorical weapon, but it properly names the reigning ideology of our era—one that venerates the logic of the market and strips away the things that make us human.

Personally, I think neoliberalism and the free market it requires are both truly bizarre ideas. After all, the ideas required by a free market that individuals will make rational choices on what to produce, what to buy, what to sell, and at what prices is strange enough. But one of the primary tenets of a free market is that all individuals involved in the buying and selling of a good or service must have all the knowledge they need to make a rational decision. Note: They must actually have all of this knowledge on hand, not just have access to the knowledge, since the other party may make it so difficult to obtain the information that mere access is irrelevent. In any case, the decision cannot hope to be rational if the parties don't have all the information they need. Besides which, just who in the hell claims that humans always, or just usually, make rational decisions in the first place?

To items I listed as forms of rentier capitalism I listed previously in What is Rent Seeking? I think it is also appropriate to consider very large executive compensation packages as rentier capitalism. Even if the compensation is tied to some form of performance requirements, whether that is share price, or profit, or some combination of these with other factors, a large part of meeting the target values is due to luck, not executive performance. For example, if the stock price goes up, how much of that is due to the effort of the CEO, and how much is due to a strong bull market?

According to Ralph Gomory and Richard Sylla in the Spring 2013 issue of Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, in 1981, when the Business Roundtable, an invitation-only association of the CEOs of the largest companies in the U.S., released its annual statement, it included the following lines:

Corporations have a responsibility, first of all, to make available to the public quality goods and services at fair prices, thereby earning a profit that attracts investment to continue and enhance the enterprise, provide jobs, and build the economy.

[. . .]

That economic responsibility is by no means incompatible with other corporate responsibilities in society.

This approach to corporate responsibility is called stakeholder capitalism, and includes employees, customers, suppliers or contractors, and the community in which corporation operates, among others.

However, by 1997, those statements had been reduced to the following:

[T]he principal objective of a business enterprise is to generate economic returns to its owners. ... [I]f the CEO and the directors are not focused on shareholder value, it may be less likely the corporation will realize that value.

The 1997 Business Roundtable statement is remarkably similar to the infamous quote by Milton Friedman in his article in the New York Times Magazine in September 1970:

The only corporate social responsibility a company has is to maximize its profits.

Soon, the boards of directors for corporations decided that, to "better align the interests of the corporate executives with the interests of the corporation," the corporations should give bonuses to executives in the form of shares, rather than cash.

With those two "maxims" in place, corporate executives quickly abandoned the idea that they should also consider all stakeholders, but only concern themselves with shareholders. Thus, the corporations switched from stakeholder capitalism to shareholder capitalism. But "shareholder capitalism" is very convenient for the executives, since they themselves have been "gifted" with a bunch of shares by the board of directors. (By the way, if you examine what board members do when they are not being board members, you will find that many of them just happen to be the CEOs and executives of other corporations. Isn't that just hunky dory for all of the executives involved in this heist of corporate wealth?)

Shareholder capitalism is also convenient for the executives because the shareholders in most corporations have very little say in the operation of the company, unless they are a large enough bloc of shareholders to place someone on the board of directors. In most cases, shareholders are limited to voting for new board members—who have been pre-approved by the existing board—, and making nonbinding recommendations on operation.

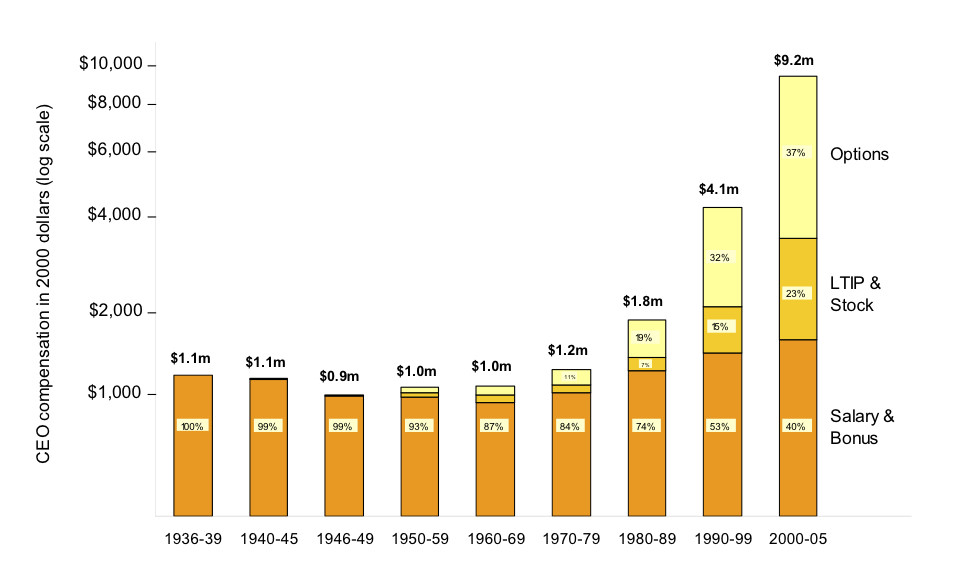

A chart, originally from a 2010 study conducted by Boston University's Carola Frydman and Stanford's Dirk Jenter, shows how CEO compensation has changed from 1935 to 2005:

The chart, published in July 2013 in Why CEO Pay Exploded Over The Last 20 Years, is already badly out of date, seventeen years later, as CEO compensation has continued to skyrocket to heights unimaginable in 1970.

By the way, a decade before the 2008 financial crisis Coca-Cola Co.’s Roberto Goizueta became one of the first CEOs to amass a billion-dollar fortune solely from "compensation" awarded to him in the form of stock options.

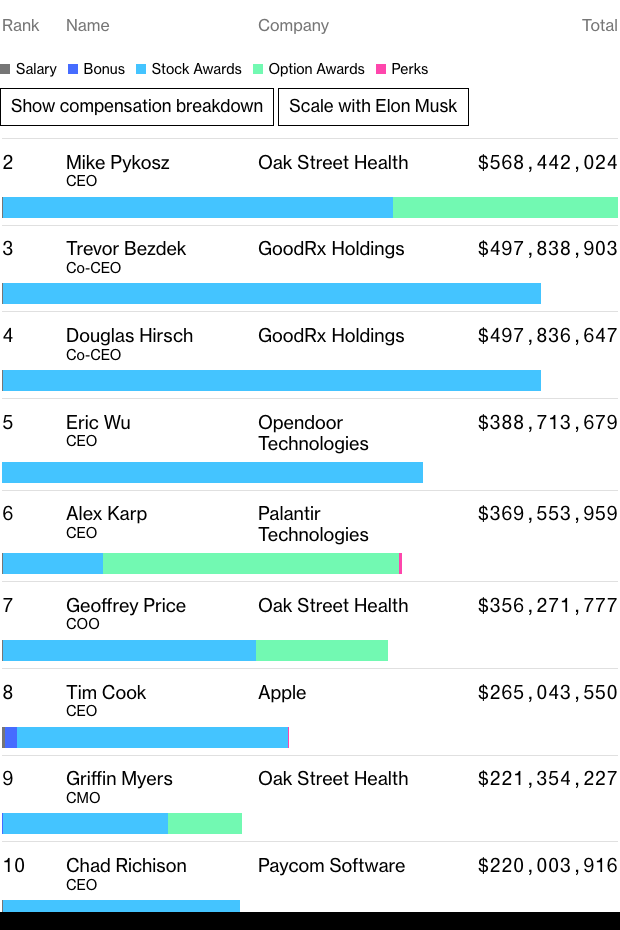

The following chart, found in Elon Musk’s Outrageous Moonshot Award Catches on Across America, which was published in August 2021, shows the top 10 highest compensated executives in the U.S. in 2020. except for Elon Musk in the number one spot at $6,658,803,818. There were at least 15 executives that year who "earned" over $100 million. The number of issued CEO awards worth at least $25 million has grown four-fold since 2016.

Mike Pykosz, the CEO of Oak Street Health, is in the number two position, below Elon Musk at number one, and two other Oak Street Health executives are also in the top 10 listing. If you have never heard of Oak Street Health before, don't worry, I hadn't either, until I saw the chart. Oak Street Health was founded in 2012, and went public in 2020. It provides Medicare Advantage programs for senior citizens in medically-underserved communities. It has 4 investors including General Atlantic and Harbour Point Capital, both of which are private equity firms. It has raised $105.3 million in funding.

Note that the number 3 and number 4 spots on the list are held by the co-CEOs of GoodRx Holdings. GoodRx Holdings says on their website: "We believe everyone deserves affordable and convenient healthcare. We build better ways for people to find the best care at the best price." The company basically provides online tools for finding the best prescription drug prices in an area, online doctor's services, lab testing services, and other services to reduce medical cost.

Medicare Advantage corporations, such as Oak Street Health, ask you to believe that they can provide healthcare to you cheaper than your government. That is mathematically impossible. They have advertising, executive bonuses, shareholder dividends, stock buybacks, and many other costs the government does not have, including taxes. It is your care that suffers. They also promised the Wall Street financial companies that own most of the shares in the companies spectacular returns and profits. And it is your health via a denial of services, medicines, and procedures that pay for their profits, dividends, stock buybacks, and executive bonuses.

I think it says a lots about our health care system in the U.S. that 5 of the top 10 most highly paid executives in 2020 were in the health care industry. It says quite loudly that our health care system is truly operating under the principles of money-for-nothing rentier capitalism.

This may be especially true in Medicare Advantage programs, where all of the advantages seem to go to the corporations, and none to the patients. As Thom Hartman reports in Time to End the Medicare Advantage Scam, the most likely reason this has been allowed to happen is that important decision-making people in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that oversee Medicare have become participants in regulatory capture, where they know they will have cushy, well-paying jobs in the very industries they are overseeing waiting for them after a few years in the government. This is classic rentier capitalism.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) compared Medicare Advantage with traditional Medicare and found the Advantage programs to be mind-bogglingly profitable: “MA insurer revenues are 30 percent higher than their healthcare spending. Healthcare spending for enrollees in MA is 25 percent lower than for enrollees in [traditional Medicare] in the same county and [with the same] risk score.”

At the same time, Medicare Advantage often screws its customers. According to the NBER study, people with Medicare Advantage got 15 percent fewer colon cancer screening tests, 24 percent fewer diagnostic tests, and 38 percent fewer flu shots.

By the way, probably 99 percent of the money made on Wall Street now is nothing but pure rent-seeking. Realize, when a company goes public, and has its Initial Public Offering of stock (IPO), all of the money that company will ever receive from the stock comes from the very first sale of each share of common stock. As each share is bought and sold after the IPO, most of that activity should be viewed as rent seeking, since it has only a tenuous connection to productivity, at best.

An extreme form of stock rent seeking occurs with high frequency trading, which is a type of algorithmic financial trading characterized by high speeds, high turnover rates, and high order-to-trade ratios that leverage high-frequency financial data and electronic trading tools. It uses powerful computers that execute millions of orders and scan multiple markets and exchanges in a matter of seconds, thus giving institutions that use these platforms an advantage in the open market. Hundreds of thousands of shares of a stock may be bought on the New York Stock Exchange, and sold a few milliseconds later on the Chicago exchange for a few pennies more per share. The computers that perform this high frequency trading are almost always located in the stock exchanges themselves, and use special high speed cables between the exchanges, none of which are available to individual traders. A connection that’s just one millisecond faster than the competition’s could boost a high-speed firm’s earnings by as much as $100 million per year, according to one estimate.

Although this article was written in January 2013, High-speed Trading: Is It Time to Apply the Brakes?, it is still fully applicable today.

In calmer times, the authors add, high-frequency trading firms hold an insurmountable edge: They can see the future. “They know what the quote of any given stock will be microseconds before those looking at the SIP [the system that disseminates quotes to the public].” No wonder firms with deep pockets pay dearly to locate their servers as close to exchanges as possible.

The fact that HFT computers know stock quotes before SIP traders also means they can "front run" the SIP traders. High-speed traders can post orders for stock in front of other inbound orders, while already knowing the ask or bid price for SIP trade. Furthermore, to incentivize bidders, exchanges pay rebates on successful bids. In this arrangement, high-frequency traders can buy and sell a share of stock at the same price, and still make profits by snaring rebates designed to lure traditional investors.

This article at Mother Jones, Too Fast to Fail: How High-Speed Trading Fuels Wall Street Disasters was also written in January 2013.

Half a century ago it was eight years; today it is around five days. Most experts agree that high-speed trading algorithms are now responsible for more than half of US trading. Computer programs send and cancel orders tirelessly in a never-ending campaign to deceive and outrace each other, or sometimes just to slow each other down. They might also flood the market with bogus trade orders to throw off competitors, or stealthily liquidate a large stock position in a manner that doesn’t provoke a price swing. It’s a world where investing—if that’s what you call buying and selling a company’s stock within a matter of seconds—often comes down to how fast you can purchase or offload it, not how much the company is actually worth.

Now, at least 50 percent of all trades are made through high frequency trading, and some trading experts claim it may be as high as 70 percent.

Investors Exchange (IEX) was created in response to questionable trading practices used by the high frequency trading programs that were becoming ubiquitous across traditional public Wall Street exchanges as well as dark pools and other alternative trading systems. IEX aims to attract investors by promising to "play fair" by operating in a transparent and straightforward manner, while also helping to level the playing field for traders. Strategies to achieve those goals include:

There is a very detailed description of the reason an exchange like IEX is needed, and how it works in The Wolf Hunters of Wall Street. The people who developed IEX found there are three ways for HFT traders to make money in highly questionable ways:

The first they called electronic front-running—seeing an investor trying to do something in one place and racing ahead of him to the next (what had happened to Katsuyama when he traded at RBC). The second they called rebate arbitrage—using the new complexity to game the seizing of whatever legal kickbacks, called rebates within the industry, the exchange offered without actually providing the liquidity that the rebate was presumably meant to entice. The third, and probably by far the most widespread, they called slow-market arbitrage. This occurred when a high-frequency trader was able to see the price of a stock change on one exchange and pick off orders sitting on other exchanges before those exchanges were able to react. This happened all day, every day, and very likely generated more billions of dollars a year than the other strategies combined.

Senator Elizabeth Warren and others, such as Senators Bernie Sanders and Brian Schatz, have proposed a small tax on each financial asset sold, including stocks, bonds, and derivatives. The exact amount of the Financial Transaction Tax (FTT) they propose varies, but is about 0.1 percent per share, or 10 cents per $100. There was an FTT in the U.S. from 1914 through 1965, and it is widely used elsewhere in the world. New York imposed a similar tax as recently as the 1980s. Several of the world’s other advanced capital markets have an FTT, including France, Italy, the UK, and Hong Kong. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) already funds its own operations through a small tax on transactions.

Although a FTT would have neglible impact on "traditional" stock trading operations, pension funds, and mutual funds, it would affect HFT trading dramatically, since HFT traders make very little money per share, but depend on high volumes to bring in the fortune. Lenore Palladino makes a strong case for implementing an FFT tax in her article, The Case for the Financial Transaction Tax in 2021.

HFT traders make the claim that HFT trading increases stock liquidity, where a liquid stock is one that has enough buyers and sellers on the bid so when you want to enter or exit a trade, you can do so quickly. But this same excessive trading is designed to manipulate the markets instead of benefiting the overall economy.

Although this increased liquidity is no doubt true, the HFT traders conveniently leave out the fact that the improved liquidity only applies to large cap stocks. Since the HFT traders make their money with high volume trades, and small cap stocks rarely have the volume needed, the improved liquidity from large numbers of trades does not happen for these stocks. In fact, HFT trading depresses the liquidity of these low cap stocks, and may even negatively affect capitalization funding for these companies.

As Lenore Palladino concludes in her article:

Our economy needs a well-functioning financial sector. As the Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has noted, our current financial system has failed at fundamental tasks such as managing risk, efficiently allocating capital, and providing funds for productive investments and job creation. Our tax system is one of many tools that can be used to disincentivize the pursuit of short-term profits over long-term stability and equity, and better align our financial sector to support the public good. Congress should not hesitate to use it.

I think there is an even more pernicious form of rent seeking when executive bonuses are given as shares, and the company then buys its own shares back, since the two events are frequently joined together at the hip, or, perhaps more accurately, joined together at the CEO's hip. Although it is largely illegal under SEC rules, the rule is never enforced.

Jan Weir writes that Stock Buybacks Are A Parasite On The US Economy. But I think it would be more appropriate to say that the corporate executives and large shareholders who push for buybacks are the parasites, while the buybacks are the tool they use to suck assets out of the company.

Stock Buybacks and Corporate Cashouts. The speaker, SEC Commissioner Robert J. Jackson Jr., was appointed by Trump, and served from January 11, 2018 to February 14, 2020.

The Origin Of 'The World's Dumbest Idea': Milton Friedman

.......

Firstly, shareholder primacy as its known didn't even exist until about 40 years ago. Before then, corps were concerned about all stakeholders, including workers, suppliers, and communities. The companies did quite well under this system. Secondly, the corporation owns its own assets. A private company became a public company when the original owners gave up ownership, and got stock certificates. These certificates outline certain rights to profits and other privileges. But this stock certificate does not contain even a hint of the word "ownership." What they got, again, was a stock certificate not a certificate of ownership. They have some rights to profits, and the company is supposed to have annual meetings where the CEO and upper management are supposed to listen to shareholders. But, in most cases, the company's mgmt can completely ignore what the shareholders want done. Although they get to vote for new directors that have been pre-approved by existing mgmt, they don't get to vote against them, or for their own slate of board members (which, incidentally, was how voting was done in the USSR). If enough shareholders refuse to vote for a specific board member, or for a new mgmt proposal, they can hope this will "embarrass" the CEO.

And, above all else, the shareholders do not face any liabilities if the corps violates laws and regulations, except, perhaps, loss of stock value.

No law—absolutely none—can be found which states that shareholders own the corporation.

Directors of public companies aren’t required by law to maximize shareholder value. Companies are formed to conduct legal activities, that’s all, and profit is not a mandatory requirement, though profitability is always an advantage.

Directors of a company have full control of it. Shareholders have no legal right to govern the activity of a company for their own benefit. Directors can decide to reduce, not increase share price, if they believe it’s in the best interest of the company itself.

Marty Lipton put it this way at an American Enterprise Institute roundtable: "I don’t view the shareholders as outright owners of the corporation in a way one would own a house or a car. They’re investors in the corporation and own the equity, and they are thus important constituents, but they are not the owners of the corporation as a whole. And for that reason the company should not be run solely in the interest of the shareholders."

As Peter Georgescu writes in the last paragraph of The Shareholders Are Not The Owners Of A Corporation:

In the end, stakeholder capitalism is one of the essential pillars of a sustainable democracy and the journey to create an equal opportunity for all future generations. That vision is worth the battles we must fight today. So, onwards.