Who are the Miculkas and Where Did We Come From?

Central Europe with the Czech Republic

Who are the Miculka's?

The Miculka surname is Czech. It is written is Czech as Mičulka, where the "č" is pronounced as "ch", as in cello and the "cz" in Czech. The symbol above the "č" is known a háček (think ha-check). Interestingly, a 'c' without the háček is pronounced 'ts' as in 'streets', while 'ch' is pronounced like the 'ch' in the Scots 'loch'. Here in Texas, in Tex-Czech, Miculka is pronounced 'Ma-chool-ka', where there is primary stress on the first syllable, and a secondary stress on "ka". In most words of more than two syllables, every odd-numbered syllable receives secondary stress. One website that provides basic information about speaking Czech has this to say: "If you take your time, Czech pronunciation can be mastered. Well, okay, maybe that's a stretch. But, it can certainly be managed." Not all online Czech pronunciation guides even agree with each other completely on how a few letters are pronounced. And then there is the letter "ř"", which has no English equivalent—another online pronunciation guide says you can pronounce it as "s", and Czech speakers will be able to figure out what you are trying to say. I have read that if you did not learn Czech as a child, you may not even hear how the "ř"" actually sounds without a great deal of practice listening to a Czech speaker say it. I listened to two different people trying to teach people how to say the Czech r, which is short rolled r similar to the Spanish r, and the "ř"". The latter sounded like an "sh" to me, until I had heard each person pronounce it four or five times, when I began to hear the slightly rolled r before the "sh." One of the instructors used Václav Havel, who served as the last president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 until the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1992 and then as the first president of the Czech Republic from 1993 to 2003, as an example of how not to pronounce the ř. In any case, this is the best explanation of how ř is pronounced that I have ever come across, Pronunciation tip: Dvořák. Perhaps, some day or other, I will be able to get it almost right. HA!

The Meaning of the Name

Last names, that is, surnames, didn't become common in Europe until at least the 18th century. While the ancient Romans used surnames, surnames fell into disuse after the fall of the Roman empire. Surnames were not used in Europe again until the Middle Ages, beginning in about the 1500's, but only the royalty had surnames, not the serfs, who went by only one name in most locations.

Although single names worked in small villages, gradually people started using second names that approximated surnames to distinguish themselves from others with the same first name in the larger villages. Nicknames were created from the names of trades, places of birth, animals, plants, personal characteristics, or months. They were given to both nobility and peasants. With time, the nicknames began to function as surnames, so they were recorded in documents and certificates, and passed from generation to generation, although people changed these "surnames" over time for many reasons.

Near the end of the 16th century, churches throughout Europe began to keep parish documents in accordance with the decisions of the Council of Trent (1545–1563). Irish parishes had started doing so earlier in the 16th century, followed by the parishes in France. This practice contributed to the stabilization of the surnames of the nobility and serfs, where virtually everyone who was not nobility was a serf.

The following types of names were most common.

Patronymic/Family—A patronymic surname was commonly adopted in England, Scotland, and Ireland to denote a person's family or father. Harrison, for example, is a patronymic surname which means "son of Harry/Harold." O'Shea meant "Of the family of Shea." In many places, patronymic names changed from generation to generation, such that a father named Jan Valentin would name his son Jakob Jan, and his son would name his own son, Petr Jakob. Eventually, patronymics began to remain the same over multiple generations. They are not widely used in the Czech Republic.

Occupational—Frequently, people took the name of the occupation in which they worked, such as, Baker, Mason (bricklayer), Thatcher, Carter, Cooper, and Paige. In the 1581 land registry for the Hukvaldy estate near Palkovice, there were the names Fojt Jan and Jura Fojtů. Fojt designates a baliff, and and Jura Fojtů was probably the son of Fojt Jan.

Habitational/Location—A habitational surname indicated where a family lived. They could take on the description of where their home was, such as Hill, or an actual town name like Durham. Other habitational surnames include Woods, Arroyo, Scott (from Scotland), and Middleton (the town in the middle).

Appearance/Characteristics—Some surnames were given to actually describe the looks, age, or personality of the bearer. Young, for example, might indicate the younger of two family members named John. Snow would mean they were light complected or had hair white as snow. Strong would mean the person had either exceptional physical strength or was forceful in personality.

Hypocoristic—Hypocoristic surnames are personal names that are shortened in spelling and pronunciation, for convenience, or the desire to express endearment. These types of names were used heavily in the Czech lands after the Council of Trent in 1763, but eventually fell out of favor, to be replaced by what we know as surnames today.

I have long wondered about what Mičulka means. But I was never able to find the meaning, until recently, when I accidentally discovered a website that claims to list all Czech surnames and their meanings. The website is familyeducation.com, and the names are listed in Czech Last Names. The database was developed by Jennifer Moss, the founder and CEO of BabyNames.com. She has a surname database at the BabyNames.com website, but it is not as complete as the database at the Family Education website, and it is much easier to find a surname at the Family Education website. It may seem strange that these sites, designed to provide parents with a wide-ranging list of possible baby first names, also list surnames. But that makes sense because knowing the meaning and history of their own surnames may help parents name their own child, and people here in the U.S. often do not have any connection to the family's place of origin.

Of course, the database does not list Mičulka, but it does list several names that are very similar to it, and all of them have a similar meaning. The names listed are: Micka, Miklas, Mikulak, Mikulas, Mikulec, Mikulecky, Mikulka, and Mikus. They are all found in the Czech and Slovak languages, and have the meaning "from a pet form of the personal name Mikuláš, the Czech and Slovak form of Nicholas." Based on this, I think it is safe for me to claim that Mičulka "is based on a form of the personal name Mikuláš."

Where is Palkovice?

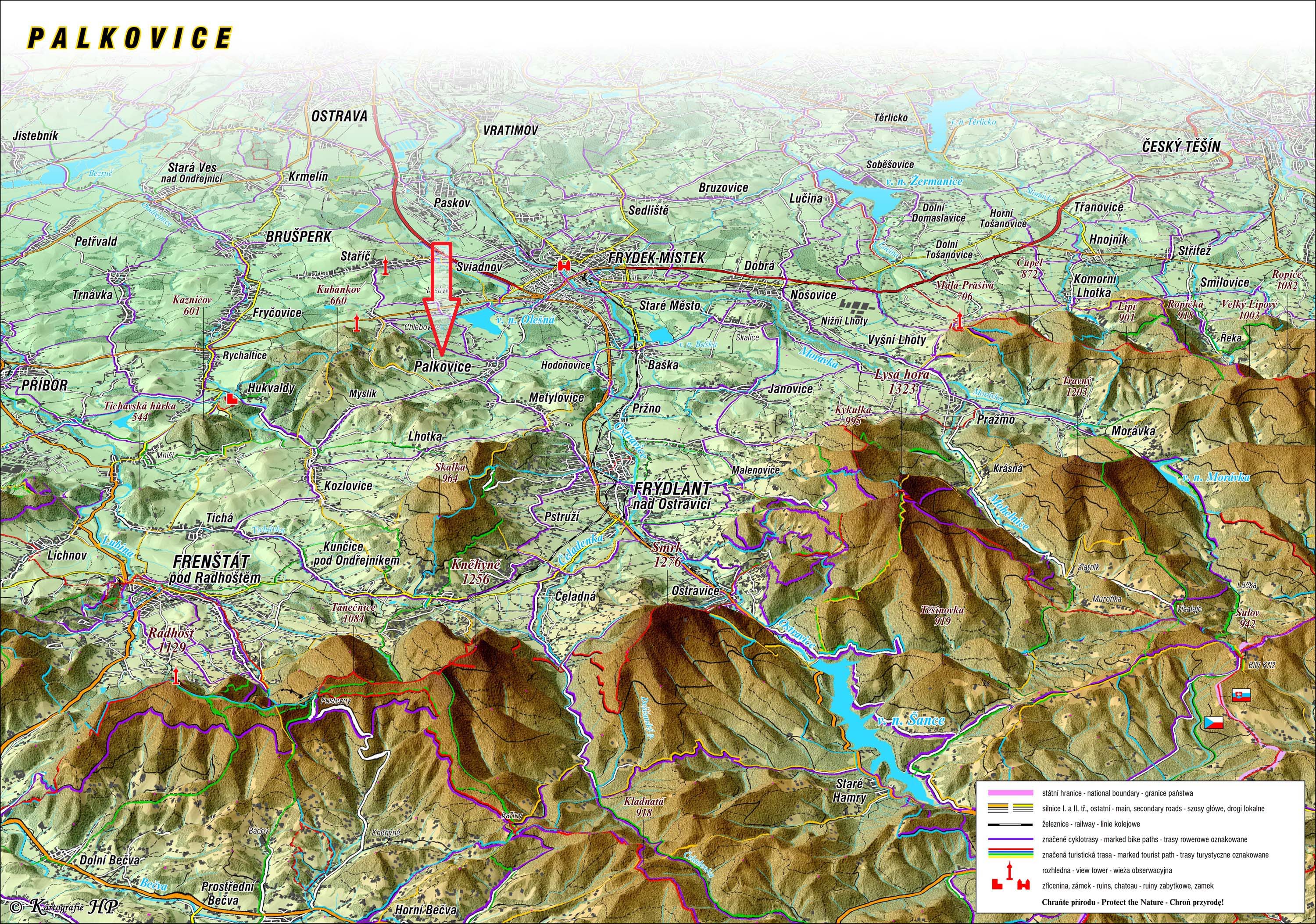

My great-grandfather and his brothers and sister came from the small village of Palkovice in what is today known as the Moravian-Silesian region in the eastern part of Czechia. Palkovice is about 170 miles east of Prague, and 15 miles west of the Polish border. The village of Palkovice consists of two parts—Palkovice and Myslík.The village has about 3,300 inhabitants, and covers an area of 2,174 hectares (or 5372 acres).

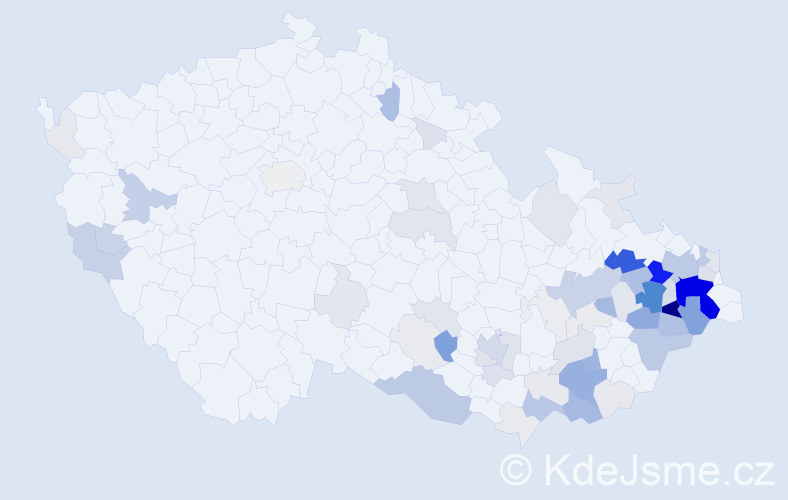

The Kde Jsme. (meaning "where are we") website gives the distribution of the Mičulka name in the various regions of Czechia. There were a total of 273 people with the Mičulka name in Czechia as of 2016. The five areas containing the largest number of Mičulka's were all near Palkovice, and contained a total of 144 people named Mičulka, or 52 percent of all Mičulka's in the country. (By the way, the US census identified 130 people with the Miculka name in the US in 2010. There are number of people with the name spelled Michulka, but the online U.S. Census database does not identify how many there were in 2010.)

Palkovice has a very informative website (https://www.palkovice.cz), as does every other town and village that I have looked at in Czechia. Of course, it is all written in Czech, and there is no English version of the website available, but I found the section on the area's history, and Google Translate seems to do a very decent translation of the "standard" Czech used at the website. Much of the following information is based on the information at that website. (Note: Since I first started developing this website less than two months ago, Palkovice now has a short webpage in English, in addition to the extensive information in Czech.)

The first record of the village of Palkovice is in 1437, although it probably existed since the first half of the 14th century, probably under a different name. A major fire in the Hukvaldy Castle in 1762 may also have destroyed records of an earlier existence. The castle is the third largest in Czechia, and is only about five miles west of Palkovice. The lord who lived in the Hukvaldy Castle controlled a vast estate that included Palkovice and Myslík, as well as Frýdek and Místek. Palkovice was a colonization village in what had been uninhabited land. By the 18th century, Palkovice was one of the largest villages in the Hukvaldy estate, with up to 1,205 inhabitants, 208 families and 191 houses. The main diet of the locals was potatoes, cabbage, milk, butter, cheese and flour, with wheat, rye, oats, potatoes, barley, clover, cabbage, apples, plums and pears were grown. The only industry in the village was 4 mills and a sawmill.

The land register in 1581 in Myslík [which is southwest of Palkovice, and is considered part of the Palkovice municipality] recorded the existence of a mill. It was supplemented with new names: Adam Červenka, Jan Adamův, Martin Adamův, Jakub Dalič, Pavel, son of the Myslík bailiff, Ondra Červenek, Jakub Hvizď, Jura Skruta, Mikoláš Mičulka, Jan Vyvial, Michal Kocich, Tomek Červenka, Pavel Blanař, Pavel Bednář, and more. Most of the data relate to the pieces of clearing caused, with the exception of Jakub Dalič, who paid 20 groschen for a grinder (that is, a mill) near his house. The subjects, who paid the benefits with a robot, worked at the lord's courts. All of the men listed can be assumed to be farmers, since it was typical of the time that only the names of farmers were listed in association with villages, not villagers, except for people such as the baliff, where a baliff carried some authority in a village or town as a representative of the lord who owned the land and property. It was also common for colonization villages to contain a large percentage of farmers while the village was being developed.

It is possible, although far from certain, that the Mikoláš Mičulka listed in the document was my very distant relative. Since this was a colonization area, he may have moved into the area to begin a new farm, but I have no idea where he came from, and I don't know when he started using Mičulka as a surname. Interestingly, from the census of fields in 1675, we learn that the village has only 10 farmsteads, 3 horticultural homesteads and 3 homesteads. We also learn the name of the Myslík mayor, Jakub Mičulka.

(Just in case you are wondering—No, robots, and even walking robots, did not refer to artificial tin men. See Robots for information.)

Palkovice and Mistek as they are seen today. The larger city of Frýdek-Místek (population 55,000) is seen in the background.

Raised relief map of Palkovice and surrounding area

Hukvaldy, Palkovice, and Frýdek-Místek

Hukvaldy Castle and Associated Village of Hukvaldy

The Hukvaldy Castle was used as the administrative center for this area until 1760. It soon fell into disrepair as stones were removed from the castle and used in local construction.